It began as a rumor. I had been on Lesbos for only one week. I’d come to see for myself what the so-called “Syrian Refugee Crisis” looked like for people on this island. I’d come to see Moria which had grown infamous in the preceding months. In my short time there I had made acquaintances on both coasts of the island; from business owners to locals who had simply lived through the worst of the crisis, to independent volunteers who had left their respective countries to come and help in any way they could. The endpoint of my daily routine was a bar in Molyvos on the North West coast called Beer Pirates. It was here where I could debrief and attempt to process what I was seeing and hearing over several bottles of Alpha, one of the local Greek beers; and it was here that I first heard about the secret refugee graveyards that were said to be scattered throughout the interior of Lesbos. Dubious of the rumors, I began to ask those I came into contact with and quickly saw that nobody seemed to have any real information at all. Then, one night, I was discussing these mythic graveyards with a fellow photographer, when a young Norwegian girl escaping a bad Tinder date plopped herself down at our table and after some explanation and pleasantries we discovered that she was an independent volunteer who had been working on the North coast. She had taken boats in during the brunt of the crisis the previous winter. “The graveyards are real. I’ve seen one. I can take you there,” she offered.

After making our way through an extremely small town, down a few dirt roads that were millimeters wider than our car, and then sliding in the warm dust under a hole in a fence, we walked through an olive grove and finally saw what, days before, was only gossip. A gravesite containing over 70 plots. Many marked. Many unmarked. Some containing multiple bodies. This was the final resting place for refugees who survived long enough to make it to shore but perhaps did not live long after arriving on Greek soil.

After making our way through an extremely small town, down a few dirt roads that were millimeters wider than our car, and then sliding in the warm dust under a hole in a fence, we walked through an olive grove and finally saw what, days before, was only gossip. A gravesite containing over 70 plots. Many marked. Many unmarked. Some containing multiple bodies. This was the final resting place for refugees who survived long enough to make it to shore but perhaps did not live long after arriving on Greek soil.

Tools of the trade: After making our way through a small town, down a narrow dirt road, and sliding under a hole in a fence, we walked through an olive grove and discovered a gravesite containing over 70 graves. Many marked. Many unmarked. Some containing multiple bodies.

This is Lesbos, and the refugee crisis is still happening here. Though the great drama of hundreds of boats landing on the North Coast is more or less over (less); the suffering, the indignity, and the legal purgatory for refugees now marooned on Lebos continue. While most of the world’s media has moved on, the suffering now exits out of sight, even for many Greeks.

Remains: Inside a tiny shack at the head of the graveyard we found a room where the bodies were washed and prepared for burial. The warm scent of rosewater filled the air.

Coming upon this graveyard was shocking, despite having braced myself for the scene. The sight raised many serious questions as to how this place came to be. This wasn’t a dirt mound or a mass grave. Someone had taken care in placing these people here. As it happens, a young Egyptian student named Moustafa Dawa is responsible for the preparation, burial, and maintenance of this “secret” graveyard.

In Mr. Dawa’s telling, he became frustrated and consumed with helplessness at what was taking place during the height of the crisis. He was working as a translator for an NGO but wanted to do more. He found an outlet for his sorrow where he believed he could make a difference. Bodies were accumulating at the Mytilini Hospital. As the story goes, among independent volunteers, local business owners, and Mr. Dawa himself; the bodies were stacked on top of one another in a refrigerated shipping container as the coroner, Theodoros Nousias, had no room at his modest facility to store all the bodies.

Unknown: For every grave that is marked with a name, there are several that look like this. Carved with only "Unknown Male" or "Unknown Female" and an age that was estimated by the coroner. Bodies were photographed, and swabbed for DNA should there ever be an opportunity to confirm their identity.

Doing what could be done Mr. Nousias photographed, DNA tested, and when possible identified the people he could. The bodies were then transported to the donated land which would become the cemetery. Mr. Dawa then prepared the bodies in keeping with the known religion of the deceased. He had headstones prepared, and buried the bodies largely by himself. Despite these efforts many of the graves are marked “Unknown.”

Unplaced: Headstones left off to the side of the graveyard. There is no evidence at the graveyard itself to suggest why these stones were not placed.

Why bodies that could be identified were not repatriated remains an open question. Mr. Dawa claims that he has been in contact with several of the families of occupants of his graveyard due to word spreading on social media. This claim could not be verified and more details about contact with these family members was not forthcoming.

Many questions were raised in my conversation with Moustafa Dawa. But it was clear to me that he had undergone a great ordeal. Like so many others still living on Lesbos, from all sides of the crisis, Mr. Dawa is forever changed by what he witnessed and the work that he has done. The island and its inhabitants have undergone a great trauma. As for the graves…

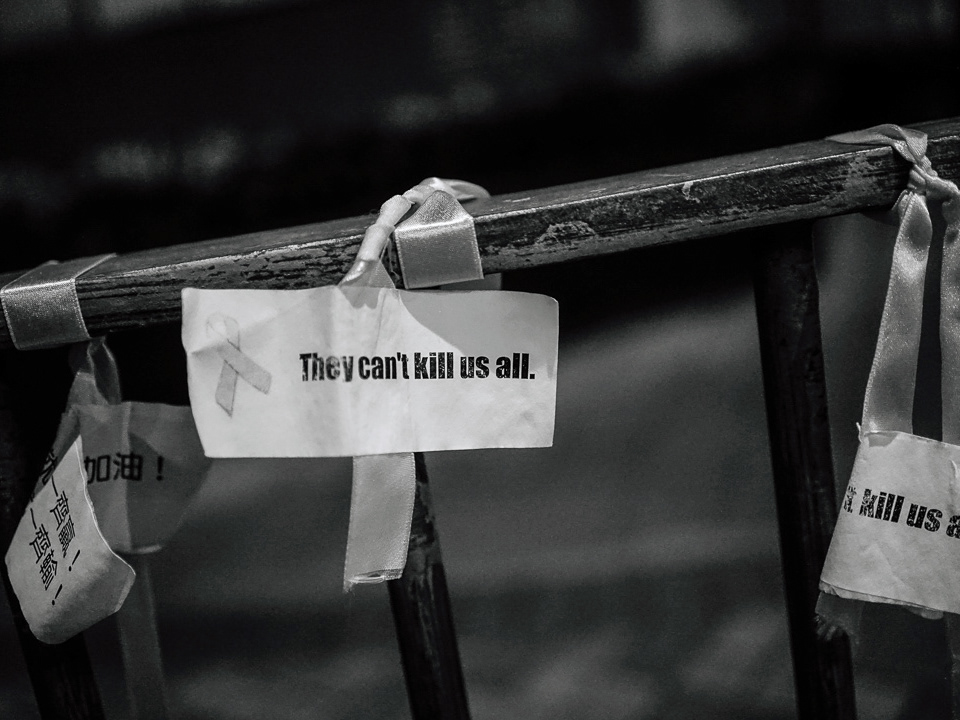

People fleeing war, deprivation, trauma and abuse struck out on an arduous and expensive journey in the hopes that their lives, and the lives of their loved ones could be lived free of war, free of violence. Their courage and their hope carried them only this far. Laid to rest by strangers, isolated and soon to be forgotten. Their aspirations for more, instead of feeding their lives, now nourish only the ground here among the olive trees.